Blog

From data to action: Insights from a high-level multilateral and donor panel on evidence uptake

Natasha Ahuja and Pedro Freitas

The 2024 What Works Hub for Global Education Annual Conference closed with a thought-provoking panel examining the challenges of evidence uptake by government systems. This session brought together perspectives from multilateral, bilateral, and philanthropic funders to discuss their role in supporting evidence ecosystems that can drive evidence-based education reform at scale.

While most funding for education comes from national governments, global funders can play an influential role by shaping incentives that impact the production and use of evidence worldwide. Earlier in the conference, policymakers discussed ways to strengthen evidence ecosystems within governments. This final session extended the conversation to focus on how funders can support and enhance these efforts.

Led by Noam Angrist from the What Works Hub for Global Education as chair, panelists Linda Jones (UNICEF Innocenti), Donika Dimovska (Jacobs Foundation), Hetal Thukral (USAID), Christine Beggs (Alternatives in Development), and Nathanael Bevan (UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office) shared insights on bridging the gap between data and action.

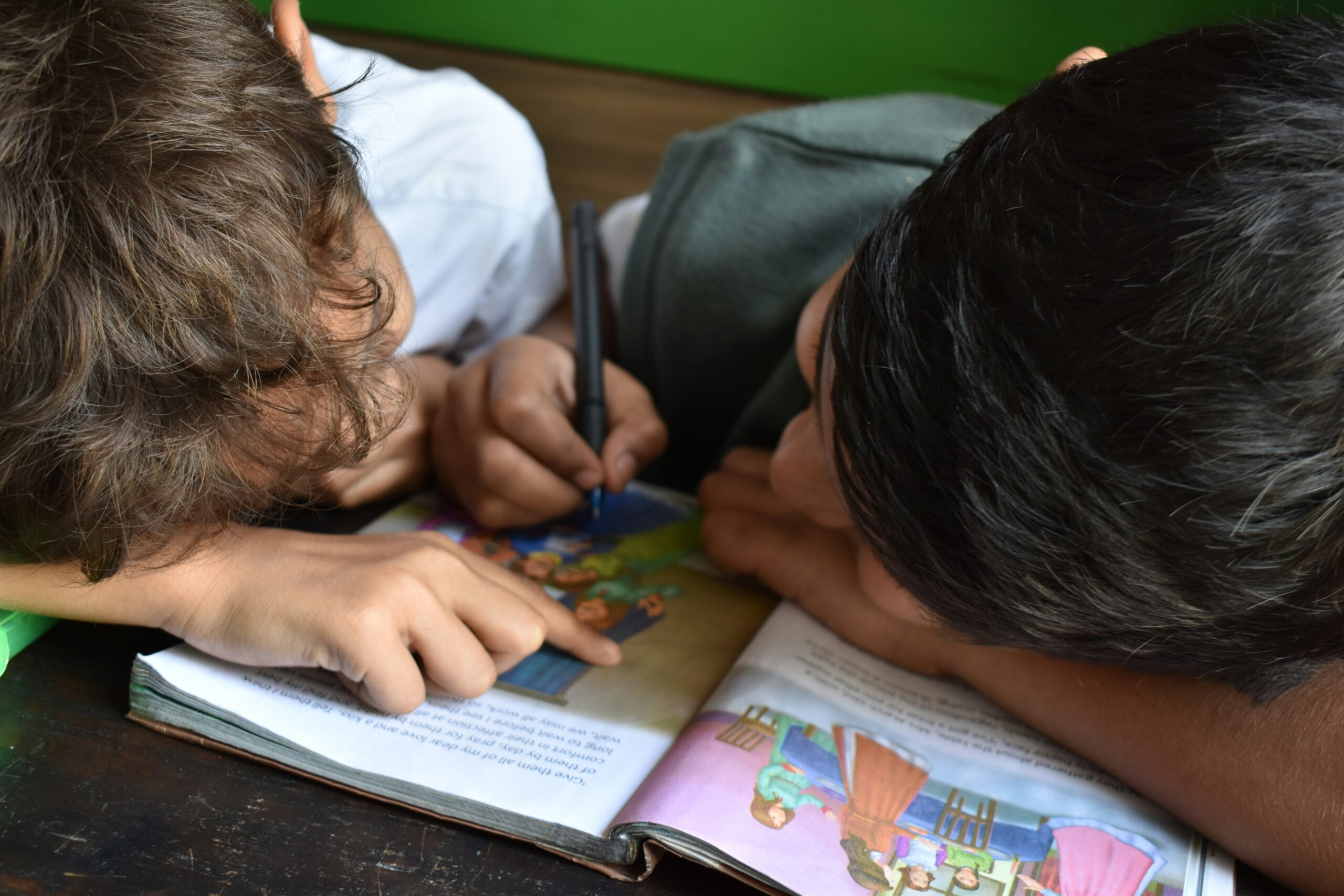

Day 2: High-level multilateral and donor panel – Evidence uptake (© What Works Hub for Global Education 2024)

Below are a few takeaways from the session.

1. A need for more research on how to make programmes scale

While we know a lot about what works, we know far less about how to make it work at scale. The Hub aims to fill this gap by advancing an ‘implementation science’ in education to support governments to implement effective educational reforms and improve learning outcomes at scale.

Christine Beggs shared why she believes this type of research is necessary: Understanding outcomes alone isn’t enough – we need to go deeper into the context of each intervention and understand how we reach the outcome. She shared an example illustrating how funders can play a role in bridging these gaps by shaping incentives. Room to Read, a global literacy organisation, received an implementation research grant to understand the impact of coaching frequency and other implementation factors on student outcomes. With this support, they systematically analysed what worked best, refining their model based on real data. ‘It was a profound experience to use data we hadn’t (used) before,’ Beggs shared, ‘it informed our (programme) design.’

Hetal Thukral highlighted another crucial dimension: ‘We need to know what works for whom.’ For example, a literacy programme may deliver strong results for some students but may require adjustments for children with diverse learning needs. Implementation research can provide these insights by examining how different populations respond to an intervention, allowing organisations to make data-driven adjustments as they scale.

By supporting initiatives that investigate the how questions – not just the what – funders can help ensure that evidence-based programmes remain relevant, effective, and impactful as they scale.

2. EdLabs might be an effective way to build bridges for evidence uptake

The question of how to ensure more efficient evidence uptake by governments was a central theme of the discussion. Several members of the panel shared why they are optimistic about EdLabs as dedicated spaces for translating evidence into policy at the country level.

Donika Dimovska from the Jacobs Foundation described why the EdLabs approach is one of their new ‘big bets’ on better utilising evidence. Aimed to function as ‘clearing houses’ for research by sorting through findings and tailoring research to meet local needs, these labs help ensure that the research aligns with government priorities from the start. ‘We keep talking about evidence-based policy, but what we want is policy-based evidence.’ she said.

Building on this, Linda Jones from UNICEF Innocenti shared how in her experience fostering trust between governments and researchers in partnership with country offices was essential for successful evidence uptake.1 This is in line with what we heard from policymakers earlier that day about the importance of trust and political context.

At the Hub, we see EdLabs as a high-potential mechanism to translate and integrate evidence into policy. Nathanael Bevan from FCDO emphasised the potential of EdLabs to facilitate evidence uptake and the need to ensure we document, codify and study the evidence uptake process:

‘EdLabs are one of those examples of ways that can help make (evidence uptake) happen systematically.’

3. Evidence translation is difficult and important work

Evidence translation plays an integral role in the research community. For evidence to reach the decision-making table, it must be communicated in ways policymakers can easily use given they are often pressed for time.2

Hetal Thukral stressed the importance of this work during the panel:

‘We often ask data experts to talk policy and policymakers to talk data. But there is a distinct role in the middle that needs to be fully recognised and supported, and it has the power to meaningfully guide decision-makers.’

We recognise the importance of making research accessible and understandable at the Hub and aim to help policymakers, practitioners and funders by synthesising, translating, and curating evidence on how to improve foundational learning at scale.3

4. Systematic reviews are useful types of evidence for evidence uptake

The panel reflected on the historical track record of evidence being incorporated into policy, and highlighted there was still a long way to go. They noted that policy choices continue to rely on anecdotal evidence, emphasising the need for improving the uptake of more robust evidence.

They highlighted the need for a ‘global knowledge base’ and more systematic reviews and meta-analyses instead of individual studies.[4] Nathanael Bevan pointed to the ‘smart buys’ report which highlights cost-effective approaches to improve learning in low- and middle-income countries as a positive example. He shared how this report proved to be useful for the Kenyan government some years ago when it sought assistance to implement structural reforms in its education sector. By providing a clear and accessible way to bring evidence to the policy table, this example underscores the value of existing evidence repositories and the importance of presenting information in ways that resonate with a broad audience.

Conclusion

As Noam Angrist reminded us at the close of the session, the panel highlighted a strong commitment to the evidence uptake process as messy as it might be, and a focus by the Hub on codifying and advancing our systematic understanding of the evidence uptake process. He emphasised the value of the Hub in bringing together funders, researchers, practitioners, and policymakers to connect the dots between evidence and action and a shared goal to make ‘the minutes in the classroom count.’

Watch video of the full session on YouTube.

Footnotes

- 1 Through UNICEF’s Data Must Speak initiative, her team found that creating strong, trusting relationships with government counterparts helped identify ‘windows of opportunity’ where evidence could be introduced in ways that resonate.

- 2 The need for evidence translation was also highlighted in the policymaker panel earlier in the day by policymakers themselves.

- 3 To read more, you can read our synthesis and evidence translation framework paper here.

- 4 Donika Dimovska stressed how we still lack a systematic process of building a ‘global knowledge base’. This gap in evidence synthesis, coupled with the ongoing pressure on governments to deliver results, as noted by Linda Jones, means that most robust evidence does not get adopted.

Ahuja, N., & Pedro, F. 2024. From data to action: Insights from a high-level multilateral and donor panel on evidence uptake. What Works Hub for Global Education. 2024/011.

https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-WhatWorksHubforGlobalEducation-BL_2024/010

Discover more

What we do

Our work will directly affect up to 3 million children, and reach up to 17 million more through its influence.

Who we are

A group of strategic partners, consortium partners, researchers, policymakers, practitioners and professionals working together.

Get involved

Share our goal of literacy, numeracy and other key skills for all children? Follow us, work with us or join us at an event.