Blog

Six insights on implementation challenges at scale – and how to fix them

Noam Angrist, Ben Piper, Rukmini Banerji, Hafsatu Hamza, Laura Poswell and Yue-Yi Hwa

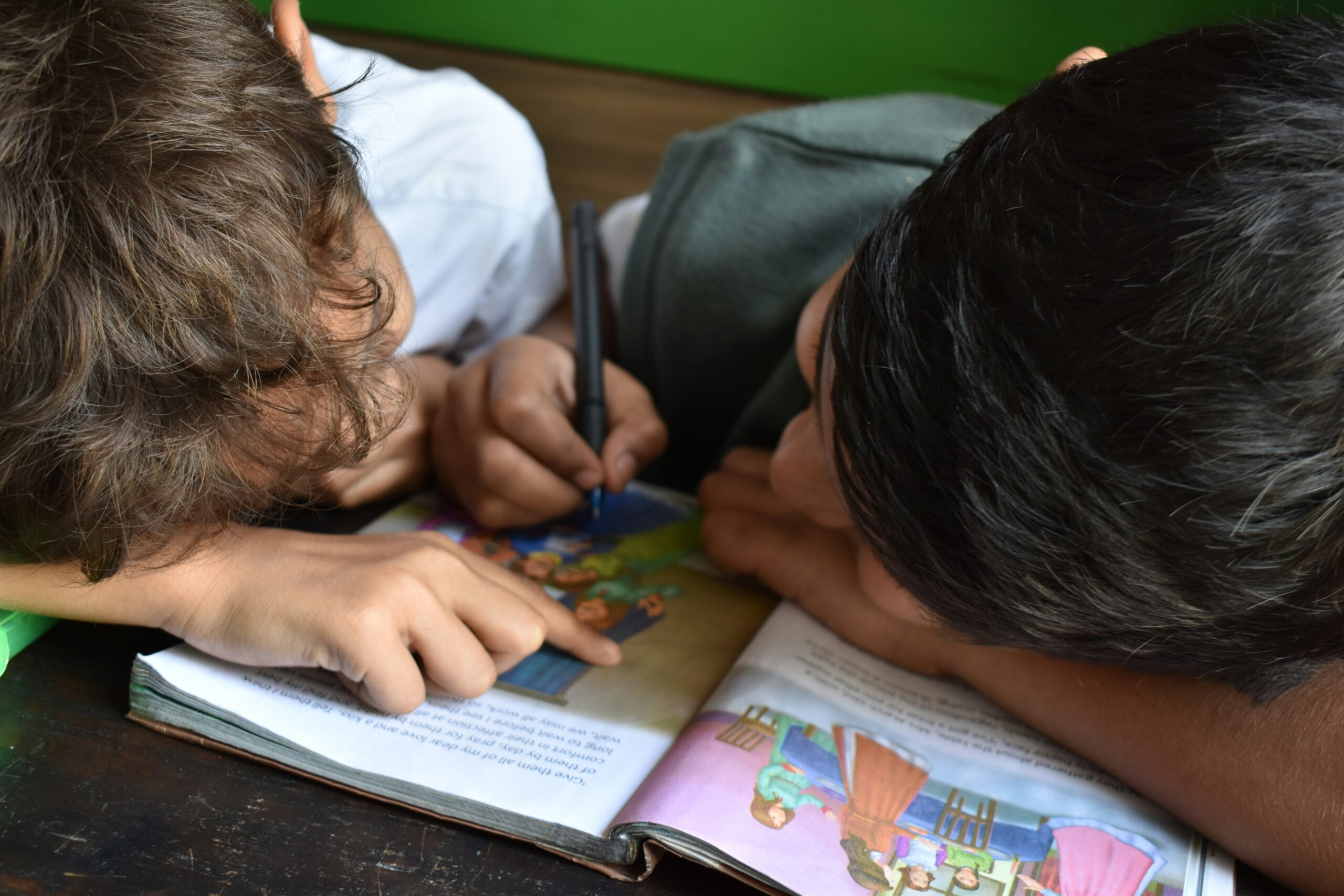

On 14–15 November, a conference marking the fifth anniversary of Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL) Africa saw many insightful panels about TaRL and other innovative efforts to cultivate foundational literacy and numeracy in the global south.

A panel titled ‘Implementation Matters: Where Do Things Break Down at Scale?’ brought together, in the words of panel moderator and Director at the Binding Constraints Lab Laura Poswell, ‘some of the most incredible programme designers and researchers that have really impacted education in the global south’. These panellists were:

- Noam Angrist, Co-Founder of Youth Impact and Academic Director of the What Works Hub for Global Education

- Ben Piper, Director of Global Education at the Gates Foundation

- Rukmini Banerji, CEO of the Pratham Education Foundation

- Hafsatu Hamza, Country Director for Nigeria at TaRL Africa

‘Implementation Matters: Where Do Things Break Down at Scale?’ Panel at the Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL) Africa 5th Anniversary Conference. (Photo credit: Noam Angrist)

Here is a selection of snippets (lightly edited for clarity) from the panel:

1. Implementation with fidelity is difficult …

We don’t always get it right. I was just in a region of Botswana that’s very successful, and I was in a classroom where the instruction wasn’t quite targeted the way you would expect with TaRL, even though it was a very good lesson with a lot of good systems in place. … The teacher had adopted the structure: a lot of the games were there, the materials were there, the grouping was there. But they were just progressing from one thing in the curriculum to the next – rather than noticing that if the kids weren’t getting a topic they should slow down. The status quo is so oriented toward a linear curriculum going from this to this to this.

—Noam Angrist

If you break down your teacher population into percentages, some percentage of teachers will always put in the extra effort. … And then there are some teachers who, no matter what you do, are never going to implement. … That leaves a large proportion of teachers in the middle who will come alongside you and implement – or go against you and not implement – depending on a few factors. A core factor is how easy the programme is. Does the teacher find some initial success to give her the sense that actually this is not that hard? But if that programme feels difficult, if it takes more time, it needs additional work, if it’s going against what the government is asking you to do, that makes it hard to implement. Often programmes struggle because they are designed for those at the top rather than the middle.

—Ben Piper

2. … but improvement is possible – especially if you are willing to learn.

There was a programme in Kenya called Tusome, which was a follow-up to a programme called PRIMR. In the first year, the results were good-ish – but not great. … As your organisation grows, there’s a real temptation to try to defend things and say that things are good. But I’m glad we took the opportunity to take mediocre results as a chance to push and say that programme implementation was okay, but if implementation was even better then we could have bigger impacts. … It was humbling to get those first results – we had worked so hard, we thought it was going to be so great, and it was only okay. But looking back, that was an opportunity to shift to a learning organisation that expects things to be difficult, that expects challenges to come, and that is defined by our ability to know what the situation is and respond to weak implementation.

—Ben Piper

One narrative that’s out there – a very sad story – is that often when things go to scale, effects dissipate. … But I’m an optimist, and I think it’s possible for effects to grow with increasing scale, even though it’s hard to achieve, if we systematically measure and improve implementation. … One example is intervention during Covid, when we adapted and implemented a phone-based tutoring intention. We did this intervention in Botswana, but also in Kenya, Nepal, India, the Philippines, and Uganda. … There was learning from experience, there was technical support, there was transfer of knowledge – and the effectiveness improved over time, even across countries. It was really exciting to see.

—Noam Angrist

3. Information flows are critical for iteratively improving implementation, but must be designed with care.

How do we measure at scale once implementation is happening? We’re tackling this at Youth Impact and at the What Works Hub for Global Education with a four-pronged strategy. First, there is randomised controlled trial (RCT) evidence as the foundation, so you can have a good amount of confidence that this has the potential to be effective. Then you monitor the theory of change at scale … you don’t have to do another RCT, but it is always nice to have some new evidence, so quasi-experimental methods are a nice approach for this. Another thing that we’re working on is finding a right-sized quasi-experimental method that uses the data that’s already in the implementation system. This is just a teaser, but we have a method in the works that we’re hoping can be used as version of difference-in-difference that makes quasi-experimental analysis easier and cheaper. Lastly, another thing that folks right now are really excited about is A/B testing, where we can randomise different tweaks to an intervention, comparing version A with version B, to make it ever more cost-effective as we scale.

—Noam Angrist

There is also a challenge of limited accountability. Many programmes struggle because you have no idea if a teacher is implementing, no idea if a district is implementing. But if you did know, what would happen? It doesn’t have to be a strong approach where you’re fired because you didn’t teach the TaRL lesson well, but there might be some light-touch reinforcement, either positive or in some cases negative, to encourage that teacher. … There are some settings that overdo the accountability, where there are incentives to inflate scores. But light-touch accountability using social influence – like the simple act of sharing information on PowerPoint about the number of visits paid by each district coach – can have an effect. It’s not about getting fired. It’s about having some indication of where we stand.

—Ben Piper

Picking up on Ben’s point about accountability, there is one state in India where they are doing Teaching at the Right Level, where the administrative unit is about 40 or 50 schools. After the midline learning assessments, they just share around at meetings the names of the top three and the bottom three schools. And it’s often not even discussed formally. It just gets everybody to be curious about who’s there and who’s not there. … I think that when it comes to what gets people to feel accountable, what gets people to feel motivated, you have to have your eyes on the ground to see how it goes.

—Rukmini Banerji

4. Government buy-in is critical – and can be fostered through local demonstrations of effectiveness.

On Tuesday, I was in Kigali at the Africa Foundational Learning Exchange 2024, and Ben happened to be on a panel. It was a huge hall, and Ben got everyone in that hall chanting: ‘Political will and prioritisation. Political will and prioritisation.’ … It really struck a chord with me, that without the political will and the prioritisation, nothing will happen. If you don’t have the government buy-in, if they don’t have the willingness to implement the programme plans, then the programme won’t really take off. Your plan is just planning to fail.

—Hafsatu Hamza

My favourite example is from our biggest state, Uttar Pradesh, which has 120,000 schools. When the opportunity came up to potentially do Teaching at the Right Level there, they said that, ‘We don’t believe in pilots. We need to see what you can do with 120,000 schools.’ … We felt that there had to be some indication of what is possible. And this indication had to come from the people who were going to lead this. … Uttar Pradesh has 75 districts. We started off by saying, ‘Bring to the table four people from each district who can lead this effort.’ So about 300 district officials came, and we spent five days with them, partly to understand who they were. If you want to bring about big change, you have to see what’s in people’s heads and what’s in their hearts. …

The real crux came after the five days with us, when they spent three weeks in their own districts doing Teaching at the Right Level for an hour a day. … In 20 days, they were able to make a difference of about 1 percentage point per day in the proportion of kids who were able to read either a paragraph or a story. … Later, when discussions happened at the highest level, they said to me, ‘Are our people really going to be able to do something like this?’ And we had data to say, ‘300 people have been able to do this.’ …

During the first five days, when they came together at the district-level meetings, or even at state-level meetings, everybody talked about how things are really difficult. ‘We have so much burden. We have to do so many things. There are so many administrative tasks. Children are poor. They don’t come to school.’ … When you visited them 15 days later, the talk was totally different. It was about, ‘You know that child in my class, when you saw him, he could do zero. Look at him now: he’s almost able to sound out words.’ There was pride in the fact that a child had changed under their watch. … You have to believe that change can happen. And now, if you’re in charge of a district, you will go hell for leather to look for and solve these problems.

—Rukmini Banerji

5. Such buy-in can be a scale multiplier, especially at subnational levels of government.

In Nigeria, TaRL in Kaduna state started off in 2022 with a pilot in one local government, with over 172 schools and 10,000 children. They were being funded by UNICEF, so it started off as a donor-funded programme. After about 2 months of implementation, they went back to UNICEF to say that they really liked this approach – and they actually expanded the pilot to two more local governments. Based on the improvements that they were seeing, they decided that, ‘We can’t wait for donor funding anymore. We need to take charge of this.’ They have now scaled up to 6 more local governments, with a total of about 239,000 children. And this is within the span of just two years. …

The other state that I want to use as an example is Kebbi. Kebbi started off by saying, ‘We’ve heard of TaRL, we’ve seen evidence of the impact on learning outcomes.’ They put money where their mouth is and started implementing it. … They ran into the normal challenges that programmes have – because they were funding it from the state government budget, they ran into the constraints of local government budgets. But because of their faith in TaRL and their belief in TaRL, they have prioritised learning improvements and have scaled it up again to four local governments, reaching about 102,000 children.

—Hafsatu Hamza

One thing that we found really interesting is what happens when leadership changes. There’s a lot of transition, both in government roles as well as in your own organisations. So how do we brace for that? … In Botswana, we’ve had six permanent secretaries in the last six or seven years. … One recommendation from the initial, visionary permanent secretary whom we worked with was building relationships with regional directors, who stay in place longer than permanent secretaries. What we increasingly have is a sandwich scaling approach, where we’re ensuring that we have the high-level buy-in, MOUs, and committees – but also really going bottom-up with the regional directors to ensure that it’s in the strategic plans of the regions as well. … And, interestingly, the regional directors rotate from region from region, so that has also spread the programme across the country.

—Noam Angrist

6. Beyond top decisionmakers, pay attention to others in the implementation ecosystem.

Another possible implementation challenge involves the mid-level civil servants. You’ve got the MoU with the regional director, you can get some individual teachers who are excited, but a lot of programmes struggle because you don’t have an entry point to that mid-level civil servant – for whom it might also feel like extra work, for whom it might also feel like it’s not in line with how they’re being evaluated. So the Gates Foundation has started to look at this question of, how do you design programs so that they are better integrated into the daily tasks of the mid-level civil servant, to get less friction from the teacher and less friction from the government?

—Ben Piper

One of the things that we’ve seen is that to improve programme fidelity, you have to look at where those challenges are. Look at the experience you’ve got in implementing, and make those corrections. What we’ve seen in Kaduna is that we didn’t include school-based management committees, so we didn’t have much community engagement. Now we are going to train those committees to help monitor programme fidelity – to bring them in to the programme so they feel really part of it.

—Hafsatu Hamza

There is a government system, but there is also a whole society, a whole community of many different people as well. So we want to work with young people in different ways as well. … The ASER survey that we do in India has been going on since 2005. It’s done in every rural district in India. … Many district-level officials, college teachers, and other actors have all have volunteered to administer ASER when they were young people. And this adds to the ecosystem of people who care about children and their learning. It helps to create a larger culture.

—Rukmini Banerji

To conclude with the words of panel moderator Laura Poswell: ‘Implementation really matters, and we have to pay a lot more homage to that than we have so far. … We need to design for the system: being realistic about what we can achieve, focusing on the areas where we can make the most impact, having the buy-in, and designing for existing structures.’

Angrist, N., Piper, B., Banerji, R., Hamza, H., Poswell, L & Hwa, YY. 2025. Six insights on implementation challenges at scale – and how to fix them. What Works Hub for Global Education. Blog. 2025/001. https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-WhatWorksHubforGlobalEducation-BL_2025/001

Discover more

What we do

Our work will directly affect up to 3 million children, and reach up to 17 million more through its influence.

Who we are

A group of strategic partners, consortium partners, researchers, policymakers, practitioners and professionals working together.

Get involved

Share our goal of literacy, numeracy and other key skills for all children? Follow us, work with us or join us at an event.