Blog

What does it cost to implement ‘just enough’ of what works to improve foundational literacy outcomes?

Christine Beggs, Hetal Thukral and Clio Dintilhac

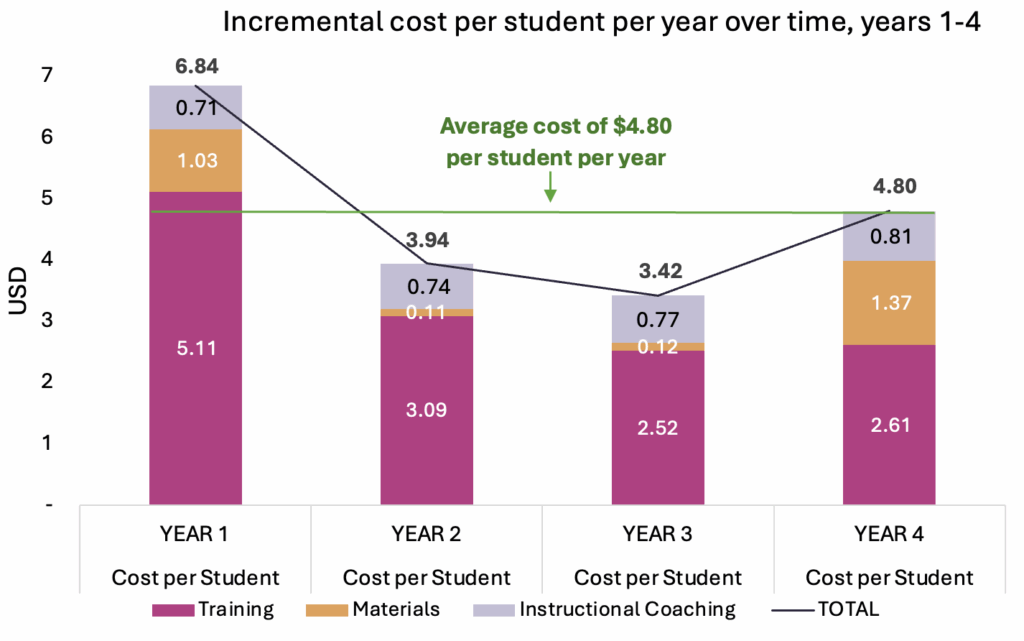

In many Sub-Saharan African contexts, a structured pedagogy model can be implemented for an estimated $4.80 per student per year (averaged over a four-year cycle).

This cost represents an increase of 1–2% over the median Sub-Saharan government investment of ~$300 per student per year in the primary cycle.

Over the past decade, evidence about how to improve foundational literacy outcomes has increased exponentially, and the evidence tells us that ‘structured pedagogy’ programmes can substantively improve foundational literacy outcomes (Banerjee et al., 2023).

Equipped with this evidence, governments and their development partners have been working to scale these programmes – and we have seen some improvements (Angrist et al, 2023), but progress has been too slow. The learning crisis is very real, with four in ten students globally and fewer than two in ten students in Sub-Saharan Africa still not meeting minimum proficiency levels in reading by the end of primary education (UNESCO, 2025a and UNESCO, 2025b).

In 2025, this learning crisis is compounded in low- and lower-middle-income countries by the dual challenge of escalating public debt that is constraining government investments in social programmes (IMF, 2025), and cuts of roughly $1 billion per year of overseas development assistance to education (Congressional Research Services, 2025). Both of these factors have disproportionately affected countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and their education systems. We need to act strategically and swiftly.

In this moment, we believe that the key question is no longer ‘What works?’ but rather ‘How do we deliver “just enough” of what works – cost-effectively and at scale through government systems?’

We see an urgent need to shift the focus from high-intensity, high-cost programmes – often funded by overseas development assistance, supported by technical assistance partners, and reaching too few students – to government-led programmes that can be delivered at relatively low marginal cost. So we set out to examine what a ‘just enough’ structured pedagogy model could look like – and what it would cost at government price levels. We also aimed to identify cost-efficiency strategies that remain underutilised in many contexts. Furthermore, this work responds to the recent clarion call for efficient and sustainable solutions to achieve foundational learning.

What is a ‘just enough’ structured pedagogy programme model and how did we arrive at this model?

A literature scan and a set of expert interviews1 that referenced an illustrative context in Sub-Saharan Africa revealed strong agreement on three components – 1) in-service professional development, 2) high-quality, well-aligned teaching and learning materials, and 3) frequent instructional coaching tailored to foundational literacy that is delivered with quality. These are familiar to all of us working on foundational literacy, of course, but what did we learn from the experts about how to optimise these components for quality and cost?

Two-Cascade, Practice-Based, Repeated In-Service Professional Development

Teachers need sufficient in-person opportunities to learn, practice and build a community with their peers. They need repeated opportunities to come together, refresh their skills and reflect on the curricula and new pedagogical practices. In this model, teachers receive seven days of face-to-face, practice-based training (80% practicum, 20% lecture) in the first year, delivered throughout the academic year. The trainer to trainee ratio is low (1:15) to facilitate practice-based learning.

In the model, head teachers and middle-tier actors participate in enough of the training to support teachers during implementation, but not all of the training, given the costs involved. After the first year of implementing new curricula and instructional routines, training continues each term to reinforce key practices and support new teachers, but with fewer days. The training model has two cascades and repeated annual training for level one trainers. A decentralised training structure reduces costs by lowering the number of overnight training participants. We share more details in the brief about the approach to professional development.

Well-Aligned Teaching and Learning Materials, Paired with Practice Opportunities

Teachers and students need sufficient high-quality, well-aligned teaching and learning materials to be successful. Teachers’ Guides should offer a consistent structure, but with varying degrees of scriptedness, depending on the skills being taught. Activities linked to student books, along with additional teacher-directed exercises that offer critical practice opportunities when supplemental materials are scarce, should be integrated into the Teachers’ Guide. In addition to these characteristics, we also heard that durability and ease of use need to be prioritised, so we included the more expensive spiral binding for Teachers’ Guides in the model.

Students also need well-structured learning materials aligned with the Teachers’ Guide. Additionally, our experts were united about the need for students to have as much reading practice as possible, so the model includes a 1:1 student textbook, with minimised space for pictures (except for grade 1) and incorporates more decodable text for practice. Given the realities of budgets and to reduce material replacement costs, the model assumes that students use a lined notebook for writing practice, referencing the textbook but not writing in the textbook.

To complement the analysis on how to improve the effectiveness of materials, we also reviewed the key cost drivers for materials and included several efficiencies in the model. First and foremost, to reduce costs, materials’ procurements should be competitive, transparent, open to international firms (possibly with a provision for local preference), and well-coordinated to allow for large print runs for each title. The brief has other interesting considerations, such as when and why colour versus black and white has a substantial impact on printing costs, how the use of artificial intelligence can reduce development costs, and how import tariffs influence the competitiveness of local and international printing.

Tailored Instructional Coaching for Teachers

The inclusion of the third component of our model – instructional coaching for teachers delivered by middle-tier staff – was less straightforward based on the evidence and interviews. Most evidence indicates, and our experts generally agreed, that instructional coaching can contribute to improvements in instructional quality and learning outcomes – but only if it is delivered with sufficient frequency and by staff equipped with knowledge and tools tailored to foundational literacy. And we all recognise that in many systems, achieving sufficient frequency and quality of instructional coaching is a long-term endeavour, requiring expensive system-level investments.

So we debated not including this component in the model given these factors but felt it was important to keep this component to signal what education systems should be aiming for in their structured pedagogy programmes as resources and system capacity allow. The model includes capacity building for middle-tier staff and three observations and coaching sessions per term per teacher. The cost model, which includes the direct costs associated with school visits, found that the incremental cost per student could be quite low with the assumption that no additional middle-tier labour investments would be required to achieve implementation.

What does this ‘just enough’ model cost?

One of the challenges our sector faces when planning for the scale and sustainability of foundational literacy programmes is the lack of reliable data on the cost to implement programmes through government systems. Most of the cost and cost-effectiveness data we have is based on pilot or small-scale programmes implemented through technical assistance partners with bi-lateral or multi-lateral funding – and unit prices that are not reflective of government prices. The reported costs of these programmes have varied widely, from more than $100 per student per year to ~$8.00 per student per year (Angrist et al, 2023, Banerjee et al 2023, and USAID, 2023), and they do not provide a good signal of what it will cost to implement at scale through government systems.

In response to this challenge, we used the ingredients method with unit prices from governments in Sub-Saharan Africa to estimate the costs of the model described above, set in an illustrative context with assumptions about existing system characteristics. We developed a new approach to organise the ingredients and costs so that we could analyse the cost of the different components, as well as costs across expense types and over time. See the brief for the full methods discussion.

What we found is that in many sub-Saharan African contexts, the model described above can be implemented for an incremental cost of ~$4.80 per student per year (on average over the initial four-year implementation period). This cost represents an increase of 1–2% over the median sub-Saharan government investment of ~$300 per student per year in the primary cycle (UNESCO, 2023). See the brief and underlying Excel cost model for additional analyses.

Figure 1: Incremental cost per student per year over time

Source: Beggs, Thukral, Dinthilac (2025).

We acknowledge that this cost model does not account for broader system capacities – such as general professional development for education staff, administrative functions, data systems, and infrastructure – that are essential for delivering education programmes. Nevertheless, we argue that it is crucial to prioritise high-impact, tightly focused strategies that governments can integrate into existing delivery systems with only a modest marginal cost increase.

We hope this work serves as a reference point for rethinking what constitutes a ‘just enough’ structured pedagogy model, and we invite others to contribute ideas about how it can be further optimised while maintaining quality. For a deeper discussion of the technical and efficiency strategies identified in this analysis, we encourage readers to consult the full brief.

1. The views and analyses presented in this brief are those of the authors alone. While they draw on existing literature and expert interviews, they do not necessarily reflect the views of any institutions or individuals consulted.

Beggs, C., Thukral, H. & Dintilhac, C. 2025. What does it cost to implement ‘just enough’ of what works to improve foundational literacy outcomes? What Works Hub for Global Education. Blog. 2025/025. https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-WhatWorksHubforGlobalEducation-BL_2025/025

Discover more

What we do

Our work will directly affect up to 3 million children, and reach up to 17 million more through its influence.

Who we are

A group of strategic partners, consortium partners, researchers, policymakers, practitioners and professionals working together.

Get involved

Share our goal of literacy, numeracy and other key skills for all children? Follow us, work with us or join us at an event.