Blog

Iterating and collaborating toward large-scale education reform in government schools: An interview with the co-founders of Leadership for Equity, India

Madhukar Reddy Banuri, Siddesh Sarma and Yue-Yi Hwa

On a recent field visit to India, What Works Hub for Global Education Senior Synthesis Manager Yue-Yi Hwa visited the non-profit organisation Leadership for Equity (LFE). Headquartered in Pune, LFE works in partnership with government with the aim of improving educational quality at scale. A third-party evaluation of their foundational literacy and numeracy project in Maharashtra has thus far found average growth of 10.7% in Marathi literacy and 19.3% in numeracy among 10,616 children in grades 1, 3 and 5 between the academic years spanning April 2021 and April 2024.

Much of LFE’s work aligns with key interest areas of the What Works Hub for Global Education, including:

- implementation at scale through government systems,

- iteration and adaptation to improve programme quality,

- strengthening the role of middle-tier officials, and

- measuring and understanding implementation and practice at scale.

To learn more about LFE’s experiences with implementing and partnering with government, Yue-Yi interviewed LFE co-founders and directors Madhukar Reddy Banuri and Siddesh Sarma.

What is the origin story of Leadership for Equity (LFE)?

Madhukar: We started out with this notion that we had to do something with governments for public schools, and something that works at scale – and that our existing efforts of working with few schools at a time were not scalable.

It was a very pleasant accident of like-minded but different people coming together. Siddesh comes from a super academic background, and he was focused on working with public systems towards about social equity. I come from a strong implementation background – I’m obsessed with the idea of leadership and how you take things to scale. So the organisation and its name – Leadership for Equity – was an amalgamation of our respective thought processes.

At the time, we had existing relationships with the Pune Municipal Corporation from supporting a teacher mentor programme. We were also starting to engage with the state government. And these relationships gave us the confidence that maybe if we set up an organisation then we could change the course of education reform in close collaboration with the system.

And from those origins, how big is Leadership for Equity (LFE) today?

Madhukar: What started off as a 12-member team in 2017 now has over 140 people across five states in India. We have a physical presence in about 34 districts in India. Our programmatic reach to date is about 250,000 teachers and educators, which also includes field officers like teacher mentors and academic middle managers in the government, with a collective reach of about 9 million children in government schools.

How did you identify the organisational niche that Leadership for Equity (LFE) works in today? Was it obvious from the start, or did it evolve along the way?

Madhukar: It was definitely iterative. When we first started, we didn’t have a vision statement of we want to do and where we want to go as an organisation. Instead, we had a bunch of projects that we brought together to form an organisation. And this led us to spend some time really thinking about what it is that we’re trying to achieve. It’s evolved over time, but what has remained constant are three of our principles.

One key principle is that in any sort of education system at scale, your teachers are the backbone. Doing any intervention without thinking about the teacher is a recipe for failure.

Second is the importance of the people who support teachers on a continuous basis. If this supporting, monitoring, and coaching doesn’t happen effectively, then no change can happen within the classroom. So we need this constant effort to build the capacity of the teacher mentor cadre, the cluster officers, the District Institutes of Education and Training (DIETs), and the State Councils of Educational Research and Training (SCERTs).

The third piece is that – even if you have great people, and you have great classroom resources – without solid policies and structures that support teachers in the longer term, none of this work is sustainable. So we need to create sustainable change by building state capacity in those institutions that are responsible for running the show, not just in nonprofits like us who are outside the government system.

Over the years, how we narrate these principles and how they shape up into projects might have changed, and our approaches have changed. But these principles have remained.

When you’re starting a new programme, where do you begin? How do you know what topics or materials are needed?

Siddesh: It’s a combination of what is requested by our government partners and what the needs analysis shows. The most in-depth needs analysis has been a three-part process that we’ve been doing in Andhra Pradesh. First, we used a detailed analysis of learning outcome data. Under a nondisclosure agreement, the state’s assessment partner, Educational Initiatives, gave us an analysis of which learning outcomes were showing the lowest performance by children.

Based on the learning outcomes analysis, we then did focus group discussions with teachers. Some focus groups were led by the LFE team, and some by government representatives. We created a questionnaire that they used to talk to teachers: ‘What topics do you think you don’t understand or do you find difficult to teach? What type of support do you need?’ And so on. In total, we conducted around 3,000 focus group discussions covering around 29,000 teachers. All of this was then auto-transcribed and put into ChatGPT to give us thematic insights.

We then divided those themes into grades and subjects, and we developed an interest survey – for example, for a specific topic that the programme could offer training on, were teachers extremely interested, interested, or not interested. About 145,000 teachers participated in that survey. Then once we had all of these data points, the learning outcomes that had the lowest performance by children and the highest interest from teachers were prioritised for development into courses.

In Maharashtra and Haryana, we weren’t able to do such a detailed needs analysis. However, we did some teacher and officer time on task studies, teacher learning interest surveys as well as sample surveys to gauge their subject and pedagogical knowledge. We also used sample-based student assessment data that we collected and publicly available data like the ASER survey reports. This helped us zero down on focus areas for the interventions.

So now you’ve decided what to focus on, how do you go about co-creating the materials?

Siddesh: Let’s take the example of training courses for teachers in Maharashtra. These are co-created with government experts. In a district-level partnership, we would work with the District Institute of Education and Training (DIET).

Previously, we used to do ‘blue sky’ discussions with the DIET. We’d say, ‘Okay, these are the main competencies that we need to focus on, based on our understanding of student data. How should we do the training? What should the scope and sequence and the session plans look like?’ These would be developed in extensive meetings and discussions with the DIET officials, and then the team would create the training materials based on what was agreed. But later we would see that there was limited uptake or maybe that the material was repetitive.

We also heard from our donors and advisors that even if you are co-creating material with government, you should have a complete set of exemplar materials with you, so that the government will know you’re coming from a place of expertise. I had previously thought that full co-creation is better, that you should not impose anything on government partners. But we found that when our field coordinators and programme managers sat with the government to understand their priorities, the feedback that we received was, ‘You don’t specialise in anything. You’re taking what we know and recycling it. So what value are you adding? We want experts to guide us and add to our knowledge.’

But we also don’t want to go in the direction of highly prescriptive programmes that succeed really well but cannot scale because they have very detailed guidelines on how the programme needs to be implemented, and maybe the first round is delivered only by the organisation’s staff.

So now what we do is create a model scope and sequence and orient our field teams on it, so that they can say to stakeholders, ‘Here is our model progression, based on research evidence. What changes do you think we should make?’ The DIET will usually change about 10 to 20% of the material, and then the course is rolled out. But sometimes the DIET completely shoots it down, saying, ‘This is some not a priority.’ Or, ‘This was already covered last year.’ And then we’d take a step back and try again.

How about getting teachers on board for engaging with the materials? What helps to build buy-in?

Siddesh: One thing that helps is that our content is hyperlocal – whether it’s teacher courses, officer courses, or something else. Because we already have good relationships with the teachers and officers, we know the archetypes of people whom we are catering to. This is similar to user-centric design.

One way we contextualise and ensure this hyperlocalisation is our review systems. For example, if someone on the content development team has written a script for a course video, then someone else who is working directly with the officers will do one round of review. Then we will get an officer – whether from the current cadre or a retired officer – to do another review and tell us whether this language and content makes sense, whether the pace works well, and so on. And we will have a review from subject-matter experts, whether from the state-level government or a third-party partner. Once they sign off, then it goes into production.

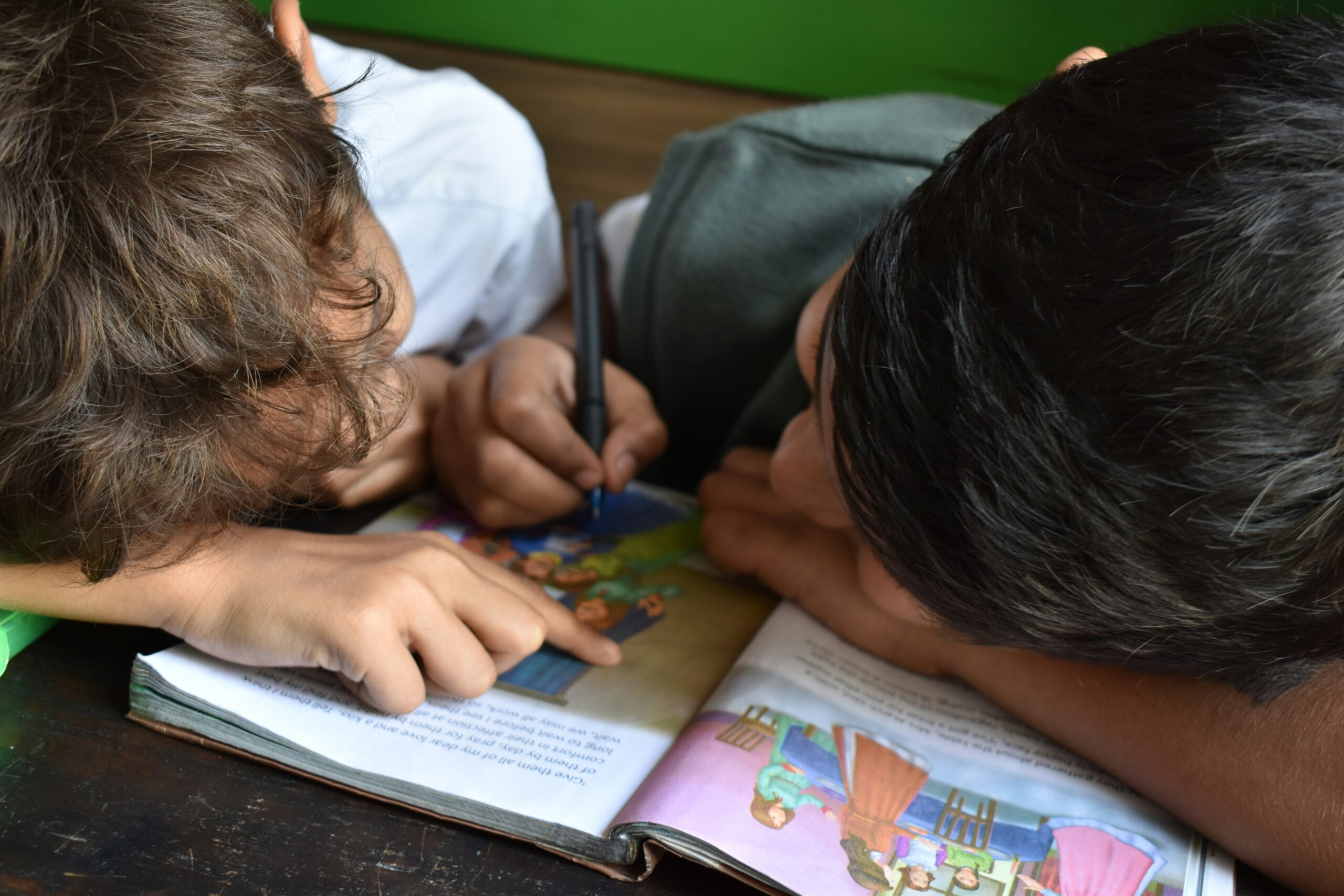

Another aspect of contextualisation is how we shoot demonstration videos. We have seen content on YouTube that teaches us a lot mathematically and pedagogically, but it’s shot in a very ‘sanitised’ studio environment, for lack of a better word. And that creates a sense of alienation, of separation from the teacher. So we go to the teacher’s own environment, and we show a positive change in that demo lesson. To show that if this can happen using these techniques in this setting with these children, then you can also do it.

We’ve gotten very, very particular about contextualised demo videos rather than studio shoots. It doesn’t have to be the most visually pleasing video, as long as it is contextually appropriate. We will pay the extra costs for production teams to travel to the villages, set up lighting and cameras, and work in the small confines of a government school. This is a non-negotiable.

That said, a challenge to acknowledge is that, at scale, we are still figuring out ways to monitor whether teachers are adopting these techniques and if not, what other barriers exist. Beyond sample observations and conversations, we have yet to understand that aspect better.

When I spoke with a decision-maker at the Maharashtra SCERT, she said that she likes working with LFE because LFE supports government projects and has the same agenda as the government, rather than promoting their own projects. But if you don’t prioritise the LFE brand, how do you demonstrate your value to funders?

Madhukar: One part of our approach is that everywhere – even in our social media communication – we always say that it is a project led and run by the government, supported by LFE as a partner. So that’s a very different tone from saying that it’s an LFE-led project with government as a partner. We do not want to be in the limelight; we would rather help increase government ownership and celebrate their success.

And if something goes wrong, we take the blame, saying that maybe we should have done things differently. That’s the price you pay for doing any large-scale work in India. And we help our funders understand all this.

Another thing we do is a constant norming and communication with government at all levels to say, ‘Look, we are doing this for the children. We’re not doing this for the money. We are a nonprofit organisation. We don’t want the credit or any public acknowledgement. It’s under your guidance and it should be scaled up under your leadership.’ This messaging, on a day-to-day basis, helps us to stay in the system.

One of the things we do for funders is we ask them to visit the sites where we work. When they hear the teachers and people inside the government talking about our work, then that in itself is a big win. Then we don’t need market ourselves because our beneficiaries are already talking about the programmes which we helped initiate and operate.

What has been one distinctive feature of your journey so far, and what are you excited about looking ahead?

Siddesh: Back in 2016, the advice we always got was to get it right for one child, one school, or ten schools and then to scale. But government schools don’t work that way. They are connected and networked in ways of functioning that prevent single-school innovations or solutions from scaling. Hence we have always tried to get the process of working at scale right, and now we are at a stage where we can embed a solution at this level. We’ll see in the next five years where this takes us both in terms of process and outcomes for education reform in public school systems.

Banuri, M.R., Sarma, S. & Hwa, YY. 2025. Iterating and collaborating toward large-scale education reform in government schools: An interview with the co-founders of Leadership for Equity, India. What Works Hub for Global Education. Blog. 2025/014. https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-WhatWorksHubforGlobalEducation-BL_2025/014

Discover more

What we do

Our work will directly affect up to 3 million children, and reach up to 17 million more through its influence.

Who we are

A group of strategic partners, consortium partners, researchers, policymakers, practitioners and professionals working together.

Get involved

Share our goal of literacy, numeracy and other key skills for all children? Follow us, work with us or join us at an event.