Blog

Universal foundational learning could unlock $196 trillion in GDP

Brad Wong, Bryce Everett, Michelle Kaffenberger and Victoria Egbetayo

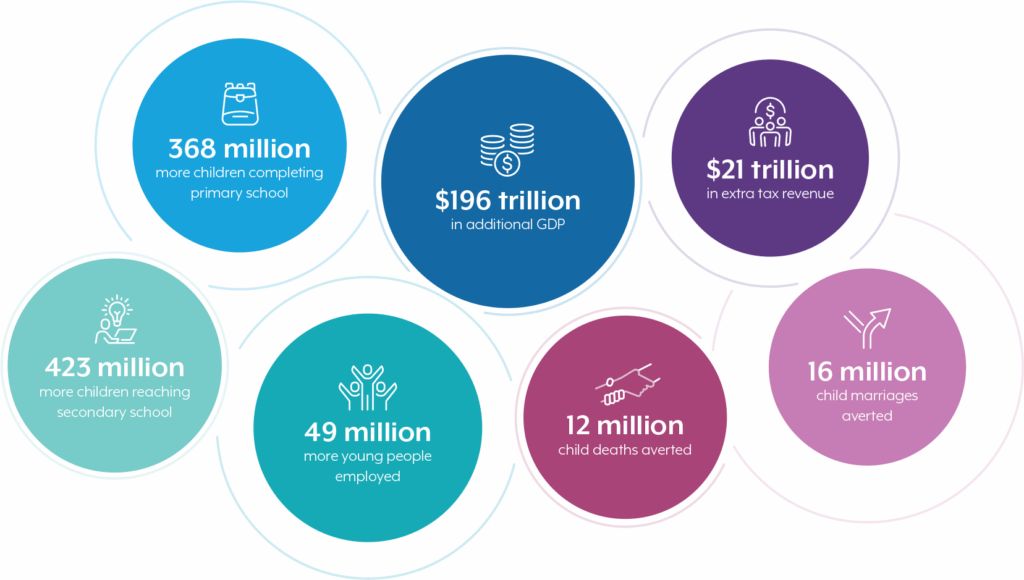

What would happen if every child could read by age 10? Nations’ economies would grow. Incomes and tax revenues would rise. More children would complete primary and proceed to secondary education. Fewer girls would be married early. Child mortality would fall. Countries would gain a clearer pathway to inclusive growth, more jobs, and long-term prosperity. This is exactly what our new research models: the transformative economic and social impact of achieving near‑universal foundational literacy.

Across low‑ and middle‑income countries, policymakers face stubborn youth unemployment, the urgency of creating high‑quality jobs, and the need to build resilient, green, and fiscally stable economies. Official development assistance is declining, and debt burdens are narrowing fiscal space. In this context, governments need evidence on what works to boost economic growth and development. Foundational learning – long treated as a basic education goal – emerges in our modelling as a core economic and development strategy.

In a first-of-its-kind modelling exercise, we simulate an increase in the share of 10-year-old children reading at minimum proficiency, moving from current country-specific levels to 90%. We then project what would happen across a range of socio-economic indicators over the period 2031-2050 for 114 countries. By achieving foundational learning our model projects:

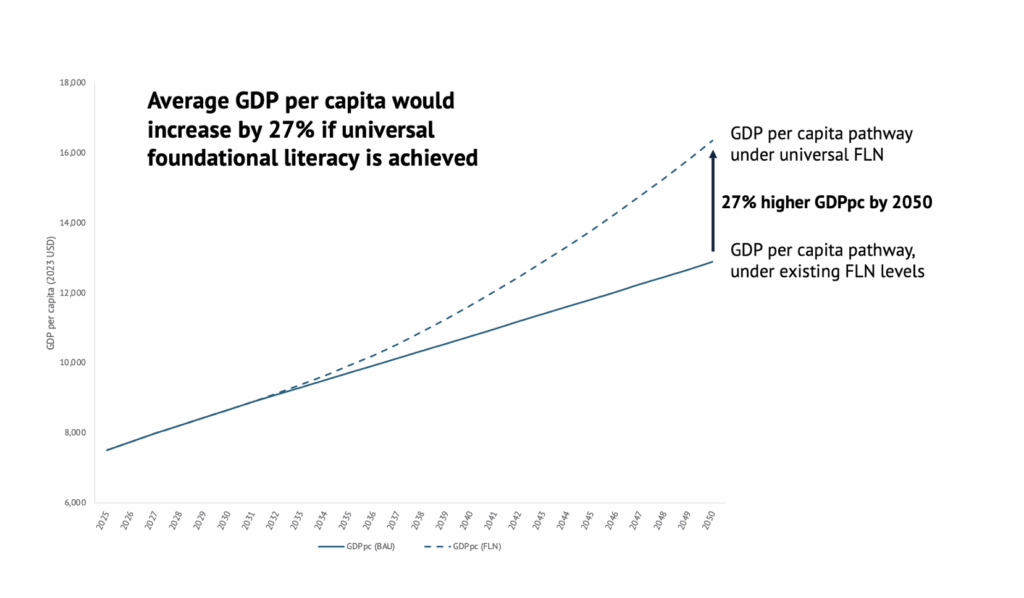

$196 trillion higher GDP – Few investments shape a nation’s prosperity more than education. And it’s not just about schooling: when children learn, countries grow faster (Hanushek and Woessmann, 2008, 2012; Angrist et al., 2021). Our analysis reveals a remarkable finding: if we achieved universal foundational learning, global economic output would increase by $196 trillion over 20 years. By 2050, GDP per capita would be on average 27% higher across the 114 countries than it otherwise would have been. Growth is a sine qua non of human development – enabling more flourishing, resilient and innovative societies.

Figure 1: Estimated Increase in GDP per capita (population weighted) if Universal Foundational Learning Achieved in 114 Countries (2023 USD, 2031-2050)

Source: Analysis by authors

$21 trillion in extra tax revenue – As economies grow, governments receive more revenue. Nations would experience $21 trillion increase in tax revenues, assuming existing tax-to-GDP ratios stay constant. That fiscal space is fuel for better services – health, education, infrastructure – and it provides the resources for nations to better deal with current and future challenges such as climate change.

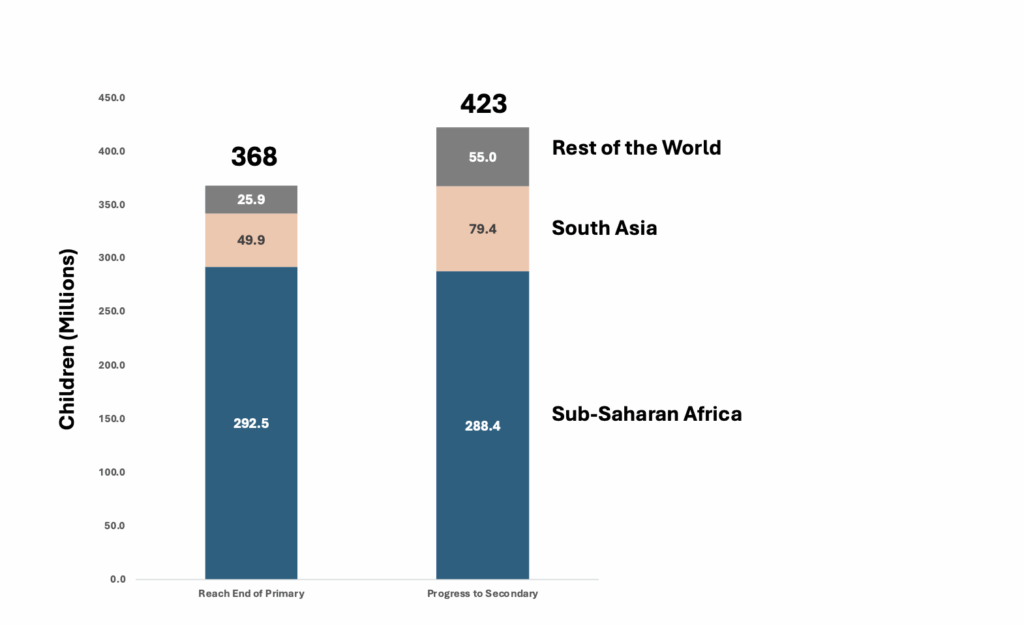

368 million additional children complete primary and 423 million progress to secondary school – Learning plays a decisive role in whether children progress through school. When students acquire basic skills early on, they are more likely to remain engaged, less likely to repeat grades, better able to keep pace with the curriculum, and less likely to drop out (Glewwe and Muralidharan, 2016; Kaffenberger, Sobol and Spindelman, 2023; Stern et al., 2024). By achieving universal foundational learning, hundreds of millions more would advance through the education system – the majority in Sub-Saharan Africa – building the pipeline of skills for modern, higher‑productivity economies.

Figure 2: Number of Additional Children Reaching the End of Primary and Secondary School if Universal Foundational Learning Achieved in 114 Countries (2031–2050)

Source: Analysis by authors

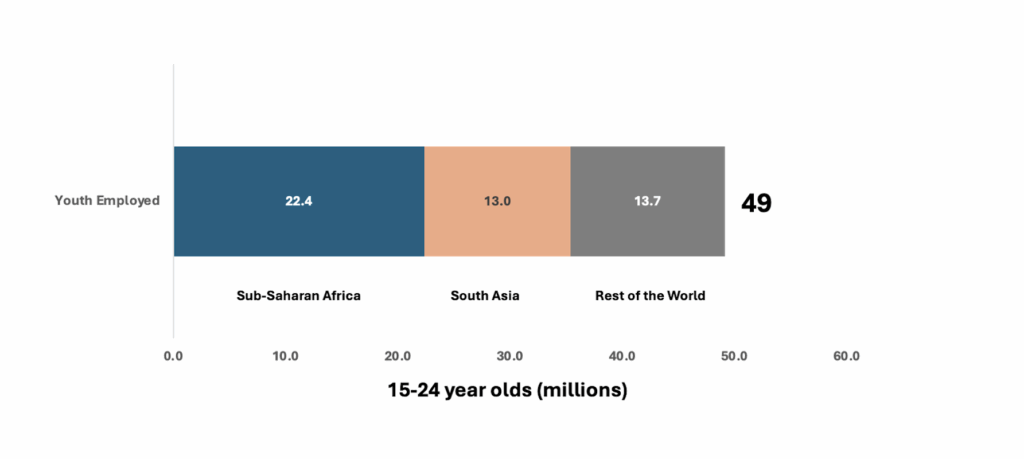

49 million more 15–24-year-olds employed – Generating sufficient, meaningful jobs for young people is one of the most pressing challenges facing governments around the world. The typical policy prescription is to support youth vocational and skills training – but these are costly and suffer from an array of challenges. Additionally, some education ministers are now acknowledging that youth possess insufficient literacy and numeracy skills to fully take advantage of technical and vocational education. Our analysis suggests that addressing the youth employment problem must start much earlier in life, focusing on foundational learning now such that in 5–10 years youth are well equipped to learn and thrive in employment. By focusing on foundational learning our model projects 49 million more youth would be employed, supporting young people and delivering wider social stability.

Figure 3: Additional Youth Persistently Employed if Universal Foundational Learning Achieved in 114 Countries (2031–2050)

Source: Analysis by authors

16 million early marriages averted – When girls stay longer in school, they are less likely to be married early (Girls Not Brides, 2025). Our analysis shows that achieving foundational learning would avert 16 million child marriages with impacts concentrated in 24 countries. The consequences would be profound: avoiding early marriage would improve the health of mothers and their children, increase decision-making authority and reduce the risk of intimate partner violence (Parsons et al., 2015).

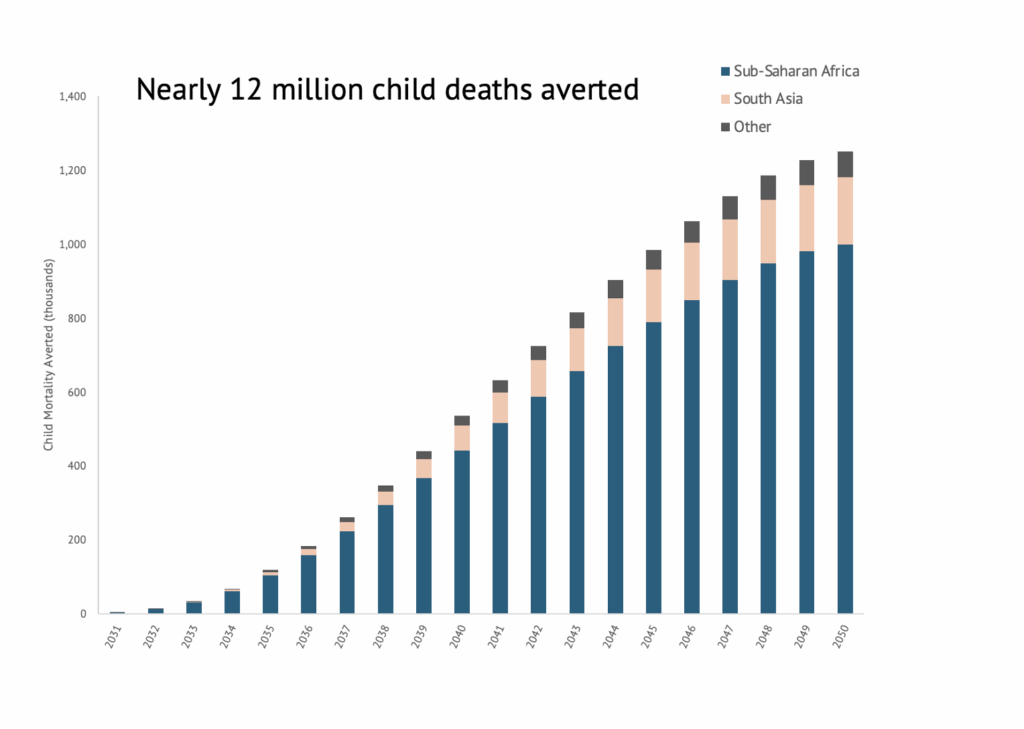

12 million child lives saved – Literacy in childhood carries forward into adulthood, shaping maternal health knowledge and behaviour and reducing child mortality (Gakidou et al., 2010; Shrestha, 2019; Kaffenberger and Pritchett, 2021). Our modelling suggests that achieving foundational learning could avert 12 million child deaths between 2031 and 2050, with the largest gains in low- and lower-middle-income countries, especially across Sub-Saharan Africa.

Figure 4: Child Mortality Averted if Universal Foundational Learning Achieved in 114 Countries (2031–2050)

Source: Analysis by authors

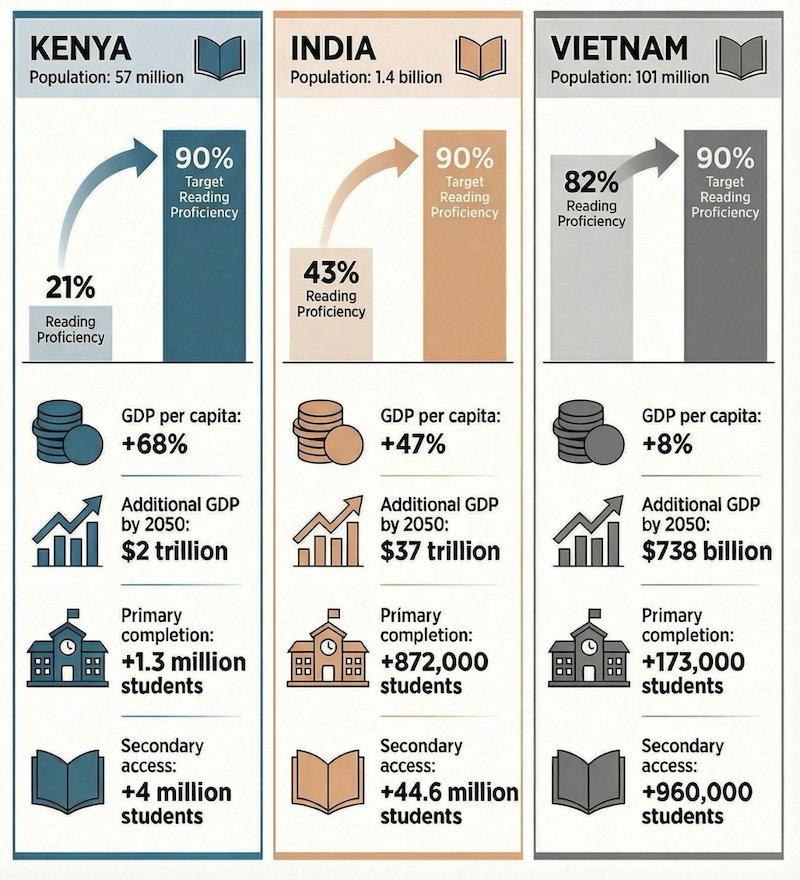

The power of foundational learning: country case studies

Our modelling provides results at the country level in addition to aggregate findings. Here we highlight three countries at different levels of baseline literacy (Kenya, 21%; India, 43%; and Vietnam, 82%). Generally speaking, the larger the gap between current literacy and the 90% target level, the greater the impacts. However, exact results are also influenced by country specific characteristics such as the enrolment levels, population size and projected economic growth. For example, because India already has high levels of primary school completion the relative boost to primary outcomes is modest, while the gains for secondary school access are very large.

Figure 5: Country Case Study Impacts of Increasing Foundational Learning to 90%, 2031–2050

Conclusion

Our modelling shows that if countries lifted foundational learning to 90%, the socio-economic gains would be transformational. Importantly, these gains tend to be largest in places where incomes and human development indicators are lowest, meaning universal foundational learning would both raise prosperity and do so in a way that narrows global inequalities. Thankfully we also know a great deal about what works to improve foundational learning. Structured pedagogy and targeted instruction (including technology-assisted personal adaptive learning) have been shown to deliver learning gains at relatively low cost (Angrist et al., 2023).

Given both the evidence and the immense political will – especially across Africa – foundational learning is the issue of our time to solve. Broader literature – such as from neuroscience and cognitive psychology – also points to ages 7–10 as key for securing strong foundational skills (Alvarez Marinelli et al., 2025). That window shapes learners’ schooling trajectories, employability, productivity, and life outcomes. With momentum building, this is not the moment to lift our foot off the gas. Delivering foundational literacy for every child is among the most powerful, cost‑effective, and future‑defining investments countries can make as part of their strategies for growth, jobs, and human development.

References

Alvarez Marinelli, H. et al. (2025) Effective Reading Instruction in Low-and-Middle-Income Countries: What the Evidence Shows. Washington DC: World Bank. Available at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/099448110272527300.

Angrist, N. et al. (2021) “Measuring human capital using global learning data,” Nature, 592(7854), pp. 403–408. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03323-7.

Angrist, N. et al. (2023) “Improving Learning in Low- and Lower-Middle-Income Countries,” Journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis, pp. 1–26. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/bca.2023.26.

Gakidou, E. et al. (2010) “Increased educational attainment and its effect on child mortality in 175 countries between 1970 and 2009: a systematic analysis,” Lancet (London, England), 376(9745), pp. 959–974. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61257-3.

Girls Not Brides (2025) Child Marriage Atlas. Available at: https://www.girlsnotbrides.org/learning-resources/child-marriage-atlas/atlas/ (Accessed: June 13, 2025).

Glewwe, P. and Muralidharan, K. (2016) “Improving Education Outcomes in Developing Countries: Evidence, Knowledge Gaps, and Policy Implications,” in Handbook of the Economics of Education. Elsevier, pp. 653–743. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63459-7.00010-5.

Hanushek, E.A. and Woessmann, L. (2008) “The Role of Cognitive Skills in Economic Development,” Journal of Economic Literature, 46(3), pp. 607–668. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.46.3.607.

Hanushek, E.A. and Woessmann, L. (2012) “Do better schools lead to more growth? Cognitive skills, economic outcomes, and causation,” Journal of Economic Growth, 17(4), pp. 267–321. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-012-9081-x.

Kaffenberger, M. and Pritchett, L. (2021) “Effective investment in women’s futures: Schooling with learning,” International Journal of Educational Development, 86, p. 102464. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2021.102464.

Kaffenberger, M., Sobol, D. and Spindelman, D. (2023) “The role of learning in school persistence and dropout: A longitudinal mixed methods study in four countries,” International Journal of Educational Research, 121, p. 102232. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2023.102232.

Parsons, J. et al. (2015) “Economic Impacts of Child Marriage: A Review of the Literature,” The Review of Faith & International Affairs, 13(3), pp. 12–22. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/15570274.2015.1075757.

Shrestha, V. (2019) “Can Basic Maternal Literacy Skills Improve Infant Health Outcomes? Evidence from the Education Act in Nepal,” Journal of Human Capital [Preprint]. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1086/704320.

Stern, J.M.B. et al. (2024) “Persistence and Emergence of Literacy Skills: Long-Term Impacts of an Effective Early Grade Reading Intervention in South Africa,” Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness [Preprint]. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/19345747.2024.2417288 (Accessed: October 3, 2025).

Wong, B., Everett, B., Kaffenberger, M. & Egbetayo, V. Universal foundational learning could unlock $196 trillion in GDP. What Works Hub for Global Education. Blog. BL_2026/002. https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-WhatWorksHubforGlobalEducation-BL_2026/002

Discover more

What we do

Our work will directly affect up to 3 million children, and reach up to 17 million more through its influence.

Who we are

A group of strategic partners, consortium partners, researchers, policymakers, practitioners and professionals working together.

Get involved

Share our goal of literacy, numeracy and other key skills for all children? Follow us, work with us or join us at an event.