Blog

The politics of learning: Reflections from primary schooling in India

Akshay Mangla

Countries across the world are faced with a learning crisis. Despite notable strides in access to education, school systems continue to suffer from low quality services, poorly trained or demotivated teachers, and weak management and governance systems. Together, these factors undermine learning for millions of children. India illustrates the scale of the challenge. Pratham’s latest Annual Statistics of Education Report finds that 25% of rural youth (ages 14-18 years) surveyed in India cannot read from a second grade textbook, while more than 50% cannot perform a basic division problem.

These learning woes cannot be easily attributed to a lack of governmental initiative. In the last several decades, India’s policy expansion and resource provisioning for primary education has been notable. This expansion focused (understandably) on student enrolments and schooling inputs, but to the neglect of quality services. The good news is that Indian policymakers recognise the need to tackle the learning crisis. India’s New Education Policy (NEP) of 2020 articulates a clear shift from schooling to learning, moving away from the ‘business as usual’ approach of simply providing schooling inputs. Instead, it focuses squarely on learning goals, encouraging the use of innovative pedagogical techniques and student assessments. It also aims for teachers and communities to work together to achieve the collective mission of learning.

The challenge lies in the political and bureaucratic processes of implementation – the translation of policies and inputs into concrete practices, services and ultimately, learning outcomes. The Indian state’s implementation capacity is chronically uneven, especially for undertaking complex tasks like student learning. More generally, efforts to achieve learning at scale must grapple with the fact that state capacity to implement quality services is often weak and notoriously difficult to build. And because the state is a political institution – consisting of interests, norms and power relations – a closer engagement with the politics of state institutions and their capacity is needed.

A focus on bureaucracy and the wider education system is important for addressing the learning crisis.

Behind the global learning crisis, the World Bank notes in its 2018 World Development Report, are ‘deeper systemic causes’, including the politics and organisation of the state’s bureaucratic apparatus. Bureaucracies in many (if not most) countries depart widely from Max Weber’s ideal of a strong, autonomous state apparatus. Many suffer from weak and politicised bureaucratic institutions. This is particularly so for ‘street-level bureaucracies’ in charge of providing local services. Under such conditions, what makes bureaucracy work, especially for the least advantaged citizens that depend on public services?

I address this question in my book, Making Bureaucracy Work: Norms, Education and Public Service Delivery in Rural India (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge Studies in the Comparative Politics of Education, 2022). My study is motivated by the puzzling subnational differences in primary education outcomes in the Hindi belt of north India, a region of sizable social inequalities, where public services are often expected to fail. Notwithstanding the same formal-legal institutions, administrative structures and national policy framework for primary education, states in this region vary significantly in how well they implement primary education.

To explain this puzzle, I advance a theory of bureaucratic norms – the unwritten rules that guide how public officials understand their duties and relate with citizens on the ground. I conceptualise policy implementation according to the complexity of tasks involved in education. I distinguish less complex, ‘codifiable’ tasks (e.g. school infrastructure construction) from more complex tasks (e.g. school monitoring and teacher academic support) involving intensive coordination between state and societal actors. My approach recognises that education services are not simply provided by states, but co-produced with input from citizens and societal groups.

Building on diverse literatures in political science, public administration and management, I develop an analytical typology, of ‘legalistic’ and ‘deliberative’ bureaucratic norms and specify the mechanisms by which they shape policy implementation. Bureaucratic norms influence how officials interpret and make practical sense of their policy mandates, encouraging certain behaviours, while discouraging others. They also have downstream effects on citizens and societal collective action around primary education. Through the mechanisms of bureaucratic action and societal feedback, bureaucratic norms impact the delivery of education services and associated outcomes.

The analysis of bureaucratic norms and state-society relations reveals the mechanisms of implementing education services in challenging environments.

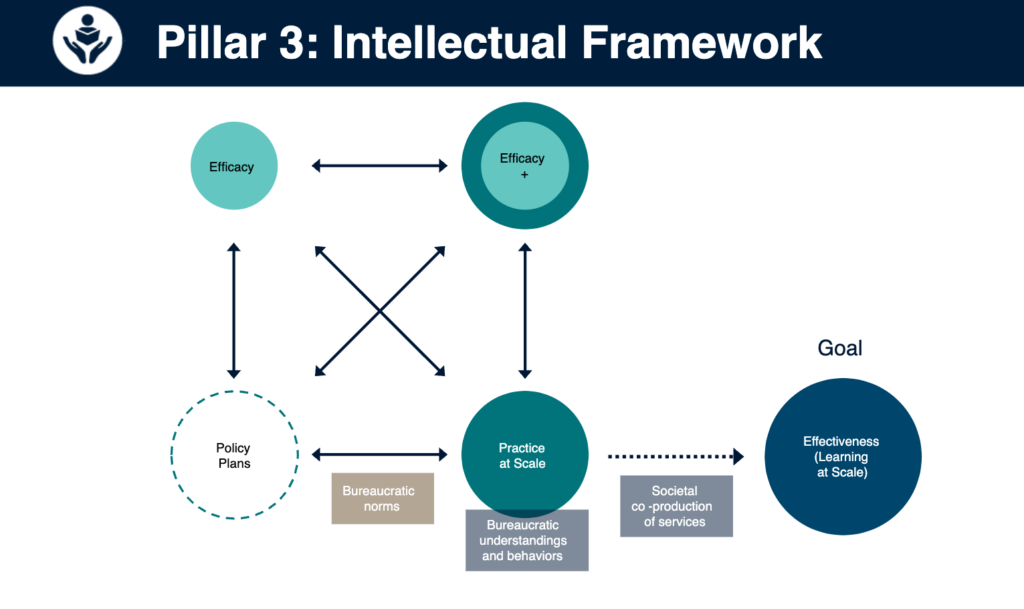

My approach adds to the What Works Hub for Global Education framework (depicted below) by tracing the linkages between education politics and policy and everyday bureaucratic practices, which in turn can influence student learning at scale.

What Works Hub for Global Education Intellectual Framework

To build and test my theoretical framework, I conducted a multi-level comparative analysis of implementation in four north Indian states: Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. The careful selection of states, local districts and villages helped to identify causal mechanisms while accounting for differences in social inequality and alternative factors that can impact public services (e.g. levels of economic development, colonial land institutions and village social capital).

The study drew upon 28 months of qualitative field research. In each of the four states, I traced the implementation process from state capitals down to local districts and village primary schools. Qualitative data came from a wide array of sources: more than 800 interviews of politicians, civil servants, local bureaucrats and schoolteachers; 103 focus group discussions with parents and village residents; participant observation inside local education bureaucracies and schools; village ethnographies capturing societal norms and local governance arrangements.

My field-based study finds that bureaucracies in some Indian states operate according to legalistic norms, which encourage compliance with policy rules. A legalistic, rules-based orientation enables some agencies to generate improvements in school infrastructure and enrolments. However, these same agencies perform poorly on complex tasks requiring coordination across institutional divisions and with society. Worse, the bureaucratic pressure to adhere to rules tends to create administrative burdens for marginalised citizens, stifling their participation in local school governance. In the state of Uttar Pradesh, for example, I show how legalistic enforcement of rules for the Midday Meal Programme – this is the Indian government’s flagship school lunch programme – often marginalise women from underprivileged castes. Over time, this process tends to weaken their engagement in programme monitoring.

In other political settings, by contrast, I find that bureaucracies exhibiting deliberative norms facilitate flexible problem-solving by state officials. Through the practice of deliberation, officials learn about how to adapt policies to local needs, which strengthens societal coproduction of services. In the state of Himachal Pradesh, I show how problem-oriented officials in the education bureaucracy made inroads with women’s groups (mahila mandals) in school governance. Collectively, local state and societal actors found ways to address practical challenges and strengthen the delivery of education services in a mountainous geography and climate. Deliberation between state and society also allowed for thicker accountability, helping to improve the quality of services for rural children.

The findings from my book resonate with recent work on local governance and education, in India and elsewhere. In her study of learning-oriented school reforms in Delhi, Yamini Aiyar reveals the overwhelming influence of a rule-following administrative culture, which resists and contorts policy efforts aimed at changing teaching practices. Likewise, Dan Honig’s study of international development agencies reveals the downsides of a compliance-oriented approach to monitoring the provision of aid. On the other hand, research examining deliberative institutional arrangements, such as village assemblies (gram sabhas), find promise in deliberation for collective problem solving for achieving social outcomes.

Future research needs to explore the motivations and mindsets of policymakers as well as the relations between state and non-state actors.

My study of education delivery in rural India also raises questions for further research. For one, it calls into question the role of political leadership in guiding and directing bureaucracy. Research on the historical roots of mass education finds that political leaders are often motivated by a desire to indoctrinate and control populations, more so than provide quality services. What, moreover, are the relationships between politicians and bureaucrats that encourage deliberation and citizen-centric policy implementation?

While my study unpacks the political origins of deliberative and legalistic norms, questions remain over how bureaucratic norms sustain over time. Furthermore, how do reformers and mission-driven bureaucrats manage resistance to learning-oriented reforms within the education system? My study of girls’ education programming in India finds that conflict and resistance, within the state but also among societal groups, can stifle the scale up of reform initiatives.

Taking stock of the literature on education reforms in developing countries, a review article finds that politics and power dynamics are central to reforms, especially when they encourage changes to teaching practices and administration. The implementation of these reforms is often contentious and opaque, while the benefits are distant and long-term. Attempts to achieve student learning require state and societal actors to make the shift from access-oriented goals to a focus on quality enhancement. Yet, the latter is particularly challenging because unlike access indicators (e.g., construction of school buildings and enrolment rates), improvements in quality are more difficult to monitor and less visible to voters.

In short, my research raises fundamental questions about the politics of learning. Going forward, research and policy initiatives aimed at improvements in learning will require a deeper engagement with the state as a political organisation and its relations with the broader system of education. This includes not just bureaucracies, but teacher unions, non-governmental organisations, religious authorities and international development agencies. A better grasp of the ideas, interests and relationships of these actors is crucial for identifying pathways for implementing reforms at scale.

Mangla, A. 2024. The politics of learning: Reflections from primary schooling in India. What Works Hub for Global Education. 2024/011.

https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-WhatWorksHubforGlobalEducation-BL_2024/011

Discover more

What we do

Our work will directly affect up to 3 million children, and reach up to 17 million more through its influence.

Who we are

A group of strategic partners, consortium partners, researchers, policymakers, practitioners and professionals working together.

Get involved

Share our goal of literacy, numeracy and other key skills for all children? Follow us, work with us or join us at an event.