Blog

How to change teacher practice at scale: Insights from a CIES 2024 panel

Yue-Yi Hwa

There is no shortage of interventions aiming to support teachers to deliver effective classroom lessons through training, new instructional materials, improved supervision, and the like. Yet many fail to trigger real changes in classroom pedagogy, let alone sustainably and at scale. These failures can be traced to a range of factors, such as issues with programme design, implementation fidelity, or sociocultural mismatches with teachers’ beliefs and classroom norms.

A panel at the Comparative and International Education Society (CIES) conference in March 2024 tackled the question of how to increase the likelihood that training and support for teachers improves classroom practice and ultimately children’s foundational learning. The panel, titled ‘Effective implementation of teacher support: Cross-context evidence and multidisciplinary synthesis on how to support teaching to improve learning’ featured speakers from different parts of the What Works Hub for Global Education – with presentations from Maleeha Hameed, Tahir Andrabi, Anustup Nayak, and Yue-Yi Hwa and discussant remarks from Kwame Akyeampong and Tendekai Mukoyi, chaired by Michelle Kaffenberger, the Hub’s head of evidence translation.

Here are some snippets from the panel:

1. Align stakeholders at different levels of the system around a shared purpose.

Evidence alone is not enough to improve teacher practices. Successful implementation also requires (among other things) aligning stakeholders from different levels in the system – such as teachers, headteachers, mid-level bureaucrats, and senior decisionmakers – around a shared goal. This was one of the key messages from a paper titled ‘A five-step approach to embedding a foundational learning program in Pakistan’, presented by Maleeha Hameed, with co-author and What Works Hub for Global Education principal investigator Tahir Andrabi.

Maleeha spoke about the political economy dynamics of embedding the Targeted Instruction in Pakistan (TIP) programme, which uses a smartphone app to make it easier for teachers to calibrate classroom teaching to children’s actual learning levels rather than their official grade level, in two districts in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Although there was clear local evidence about the gap between children’s learning outcomes and the grade-level curriculum, alongside clear international evidence about the promise of targeted instruction for closing such gaps, the process of embedding targeted instruction in teachers’ classroom practices still took extensive consensus building and political savvy. As Maleeha observed, it’s not just about engaging stakeholders top-down or bottom-up, but working in multiple directions at once.

Aligning stakeholders at multiple levels – e.g., teachers, middle-level officials, high-level decision-makers

An earlier version of Maleeha and Tahir’s paper is available online, along with a blog with photographs of TIP in action. Tahir and the other members of the Hub’s Pakistan research team will continue to study TIP, focusing on another vital aspect of implementation at scale: how the intervention is (or is not) diffusing to different classrooms and schools over time.

2. Individual relationship building is a powerful tool.

Reflecting on Youth Impact’s experience of scaling up the Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL) programme from several dozen schools in Botswana to half of all schools in the country, Tendekai Mukoyi discussed the importance of bringing as many stakeholders as possible along on the journey. Youth Impact’s ‘implementation systems’ approach included not only building relationships with top government decisionmakers but also speaking with cleaning staff in schools, so that they would be on the same page about the afterschool TaRL sessions that inevitably affected cleaning schedules.

Tendekai also noted that it was important for researchers and implementing organisations to steer away from approaching new implementation contexts as experts with all the knowledge. Rather, they should act as co-creators who want to speak with teachers to understand their challenges and develop shared goals.

With the What Works Hub for Global Education, Youth Impact is continuing to expand the evidence on scaling targeted instruction with teachers, including through A/B testing and other rapid evidence approaches.

3. Working with teachers’ beliefs helps embed new practices.

A recurring theme on the panel was the importance of understanding, working with, and shaping teachers’ beliefs and perspectives to enable new teaching practices. In the other set of discussant remarks for the panel, Kwame Akyeampong, a principal investigator for a What Works Hub for Global Education project in Ghana, emphasised how important it is to understand teachers’ thinking. He noted that there had been more research in this area in the global north than the global south.

Practically, Kwame observed that one entry point for engaging with teachers’ beliefs alongside programme implementation is creating communities of practice where teachers can share their thinking with each other and develop together rather than working in isolation.

Another entry point is initial teacher education. Teachers’ beliefs about education emerge during their own school years and continue to evolve during their pre-service training. Working toward alignment between pre-service and in-service training – along with other programmes and interventions that teachers will encounter in schools – will help beginning teachers to transition smoothly into classrooms and sustain their passion for teaching, rather than becoming jaded by classroom realities.

4. Effective support for teachers needs to work with existing structures like the school calendar.

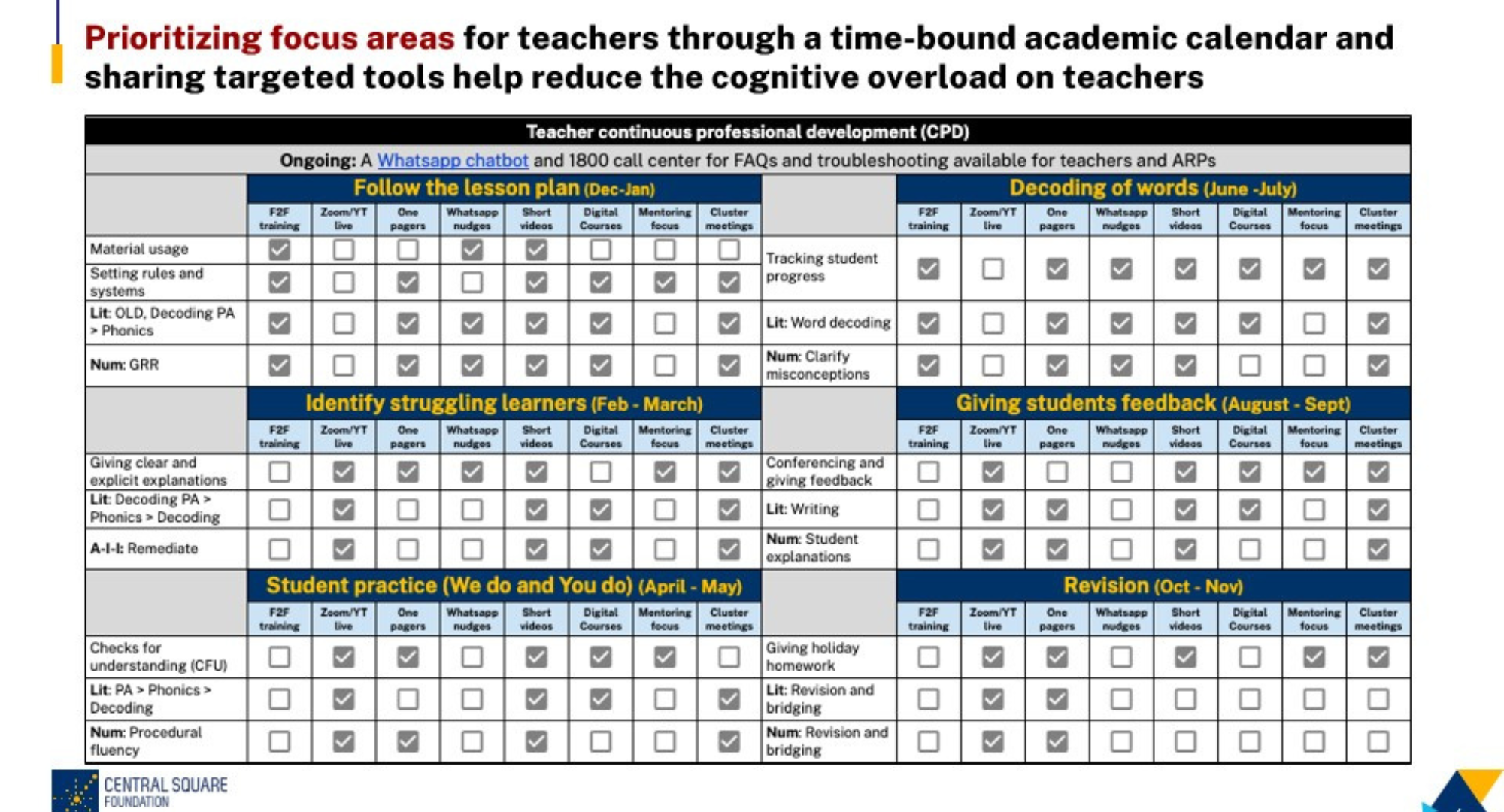

Besides working with different phases of the teacher career timeline, programmes should also work with the rhythms of the school calendar. This is one of the many design features of the Central Square Foundation’s work to support teachers in cultivating children’s foundational literacy and numeracy, as outlined by Anustup Nayak, a member of the What Works Hub for Global Education’s Community of Practice steering committee, in a presentation titled ‘Supporting teachers to maximise learning outcomes through structured pedagogy programmes’.

Anustup described an ongoing project with the state government of Uttar Pradesh, India, to support teachers to change their instructional practice in line with a structured pedagogy programme. As Anustup noted, teachers make hundreds of pedagogical decisions throughout each school day. They are often overloaded with information and feel that their support systems are inadequate.

Aligning structured pedagogy to the school calendar

This project in Uttar Pradesh aims to give teachers the support they need, when they need it. The support package is aligned with the school calendar, simplifying what teachers need to keep track of. By managing the sequence of professional development focus areas and messages that teachers receive, the programme helps teachers to change their practices cumulatively, rather than contributing to the information overload. Within each focus area, teachers are provided with an interconnected set of tools, including training, teacher guides, prompts via WhatsApp messages, micro-videos illustrating specific classroom practices, and an on-demand chatbot. Some of these resources are available on the Central Square Foundation’s public goods website.

5. Programmes should continually iterate and adapt over time and as they scale.

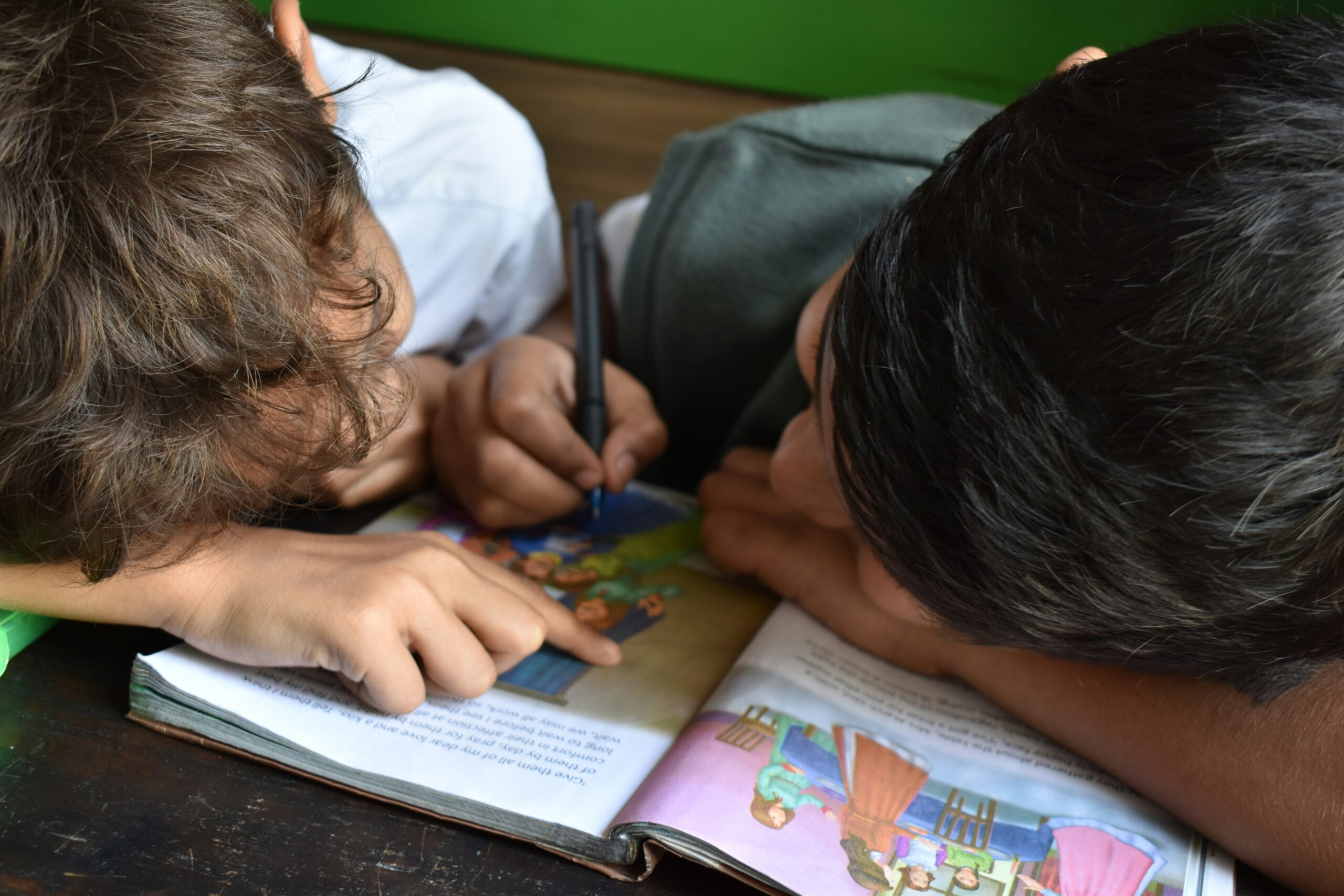

It is clichéd to say that context matters in education and in policy implementation – but clichés can be true. In the final presentation of the panel, titled ‘Effective support for teachers in the global south: Tools, training, and feedback channels for cultivating children’s learning at scale’, I spoke about an ongoing project under the synthesis and evidence translation pillar of the What Works Hub for Global Education. This work-in-progress is a study that looks across diverse programmes that have effectively supported teachers to cultivate children’s leaning – in order to identify the ‘core components’ that are common across these seemingly different programmes in driving the success of such teacher support.

One core component that is evident across effective programmes is that implementers and programme designers intentionally adapt the programme to suit the context.

Crucially, such adaptation and optimisation isn’t a one-off activity. Context doesn’t stop mattering after the pilot phase. Rather, adaptation must be an iterative, ongoing process. Iteration on programme design needs to occur continually over time because implementation contexts can change – whether with successive cohorts of students and teachers, or as a programme interacts with existing structures and norms and evolves in unexpected ways, or as it is scaled up to other settings that differ in consequential ways.

Continual iteration and adaptation to context

Iteration is also needed because researchers, policymakers, and implementers should be constantly learning more about education and education systems and how things work and why and for whom. Here’s to continual refinement of our collective knowledge about implementation in education – and to continual growth in the number of classrooms throughout the global south where children have meaningful opportunities to learn what they need to thrive in education and beyond.

Hwa, YY. 2024. How to change teacher practice at scale: Insights from a CIES 2024 panel. What Works Hub for Global Education. 2024/002. https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-WhatWorksHubforGlobalEducation-BL_2024/002

Discover more

What we do

Our work will directly affect up to 3 million children, and reach up to 17 million more through its influence.

Who we are

A group of strategic partners, consortium partners, researchers, policymakers, practitioners and professionals working together.

Get involved

Share our goal of literacy, numeracy and other key skills for all children? Follow us, work with us or join us at an event.